Synthroid is a T4-only thyroid medication used to treat hypothyroidism.

It’s not as commonly prescribed as levothyroxine (which is its generic version) but there are a lot of patients out there using this medication.

But just because it’s commonly prescribed doesn’t mean it’s the best option or that it’s without faults.

If you’re taking Synthroid, here are 10 things that you should know:

DOWNLOAD FREE RESOURCES

Foods to Avoid if you Have Thyroid Problems:

I’ve found that these 10 foods cause the most problems for thyroid patients. Learn which foods you should avoid if you have thyroid disease of any type.

The Complete List of Thyroid Lab tests:

The list includes optimal ranges, normal ranges, and the complete list of tests you need to diagnose and manage thyroid disease correctly!

#1. Synthroid Is Inactive

As a thyroid medication, Synthroid comes in an inactive form.

Yes, your body can activate it, but that requires a few extra steps, and not everyone does this equally well.

This activation process is referred to as thyroid conversion and it’s a big stumbling block for many people taking T4-only thyroid medications like Synthroid and levothyroxine.

What does this mean for you?

It may be entirely possible that you are taking Synthroid faithfully and it is being actively absorbed in your body BUT it is not being activated in your tissues.

This process may lead to persistent symptoms of hypothyroidism despite having normal thyroid lab tests and a normal TSH.

So what causes peripheral thyroid conversion issues?

Well, glad you asked!

It’s actually an evolving topic but we know for sure that these factors may contribute:

- Genetics – Sometimes genetics work for you and other times they work against you. It turns out that some people have mutations in the enzyme responsible for the conversion of T4 to T3 which make it work less efficiently. Individuals with this genetic mutation, known as a SNP, will not convert T4 to T3 as well as other individuals. Currently, the testing for this SNP is not standardized but you can make educated guesswork based on thyroid labs.

- Medications – It is well known that certain prescription medications may interfere with thyroid conversion. Medications such as anti-hypertensives, diabetic medications, and seizure medications are all included in this list. If at all possible it may be worth a look at your medication list to determine if you can consolidate medications or even change medications to see if it improves thyroid function.

- Inflammation – Systemic inflammation from any cause may reduce T4 to T3 conversion in the peripheral tissues. You can assess for systemic inflammation with serum markers such as ESR, CRP, and ferritin.

- Intestinal issues – A large portion of circulating T4 is actually converted into T3 in your intestinal tract known as the “gut”. Therefore it makes sense that certain intestinal diseases may limit this process. If you suspect peripheral thyroid conversion issues you should evaluate for conditions such as acid reflux, intestinal dysbiosis, SIBO, IBD, and IBS.

- Endocrine disruptors (the environment) – Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that humans come into contact with on a daily basis and are found in plastics and other manufactured products. Small amounts of these chemicals don’t seem to cause a problem for most people but certain individuals (probably due to genetics) may be particularly sensitive to them. Furthermore, studies from the endocrine society have shown that these chemicals alter serum thyroid lab markers and may make interpretation of these tests difficult.

#2. Synthroid Will Only Work If It’s Absorbed

Another important consideration is the topic of absorption.

Meaning: are you actually absorbing the medication that you are taking?

It sounds silly, and many people just assume that they are absorbing their medication without a problem but that may not necessarily be true.

Do you remember what the pharmacist tells you when you pick up your medication?

They probably remind you to take your medication on an empty stomach or first thing in the morning (this is fairly standard).

They want you to take your medication on an empty stomach because that gives your body the best possible chance of absorbing as much medication as possible.

Taking Synthroid with food, medications, supplements, and juices/drinks/coffee may impair intestinal absorption of your medication.

Why is this important?

Because if you are taking 100mcg of Synthroid you want to make sure that that 100mcg makes it into your body.

If you take it with food then you might only be getting 80mcg of the 100mcg dose.

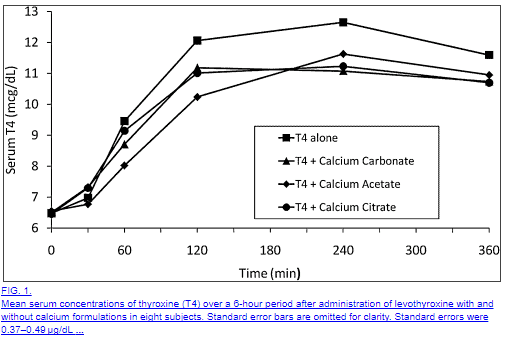

Here is a list of medications that are known to reduce Synthroid absorption (5):

- Iron Salts

- Calcium carbonate (6)

- Sucralfate

- Aluminum-containing antacids

- Raloxifene

- Chromium picolinate

- Sevelamer

- Colesevelam

- Lanthanum carbonate

These medications include only those medications that limit thyroid ABSORPTION but remember that there are others that interfere with thyroid conversion as well.

You may have noticed that this list includes very common medications such as those that contain iron (often used to treat anemia), calcium (often used to treat osteoporosis), and antacids (often used to treat acid reflux).

If you are taking Synthroid, make sure that you are taking it away from medications that may limit its absorption!

You can avoid these pitfalls by making sure that you take your thyroid medication in a “fasted state” which has been shown to ensure more stable TSH and serum thyroid markers (7).

#3. Are Supplements Rendering Synthroid Ineffective?

Certain supplements can impair the absorption of thyroid hormones.

While other supplements may actually improve thyroid function.

Guidelines to stick to if you use supplements with Synthroid:

- If you need to take iron or calcium make sure that you allow at least 4 hours after you take these supplements before you take Synthroid.

- Iodine can help (or hurt) thyroid function – only use what is appropriate for your body and based on your natural intake of iodine from food sources.

- Take no more than 5-7 supplements in total each day.

- The combination of selenium and zinc may help improve peripheral thyroid conversion in individuals who are deficient in these minerals, you can read more here.

#4. The Time Of Day That You Take Synthroid Matters

Don’t get frustrated with me here because I’m about to say something that may run contrary to what you know about taking your thyroid medication…

And that is this:

Sometimes it’s better to take your medication in the evening as opposed to taking it in the morning.

But didn’t I just say that you needed to take your medication in the morning on an empty stomach to increase absorption?

Yes and that is still true, but this new information is also true, just for different reasons.

The idea behind taking your medication first thing in the morning is to help increase absorption because you will be in a fasted state – meaning you won’t have food to compete with the absorption of food in your stomach.

But there is one problem with this idea and it has to do with the speed of your intestinal tract in the morning vs in the evening.

Your intestinal tract is actually more active in the morning, meaning it is faster, and therefore your medication (and food) will spend less time in the small intestines where it is absorbed.

And this should make sense especially when you consider that most individuals have their bowel movements in the morning, this is because of the speed of the GI tract.

So what’s different about the evening?

In the evening your GI tract slows down which means that Synthroid, and other medications, will spend more time in your intestines which may, therefore, increase absorption.

And studies have actually shown this to largely be true as well.

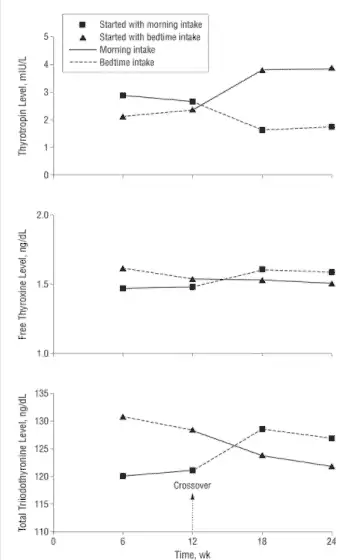

One study (which tested levothyroxine) showed (8) that taking thyroid medication in the evening significantly improved thyroid hormone levels of both free T3 and free T4 and showed a drop in TSH (labeled as Thyrotropin).

And another study showed (9) that taking thyroid medication in the evening is at least as efficacious as taking it in the morning and may actually increase quality of life metrics in certain patients.

The moral of the story?

There really isn’t a downside to switching up the time of day that you take your thyroid medication but on the flip side, you might actually realize some serious benefits.

#5. How Synthroid Compares to Levothyroxine

The most commonly prescribed formulations of thyroid medication include the brand name Synthroid and the generic version levothyroxine.

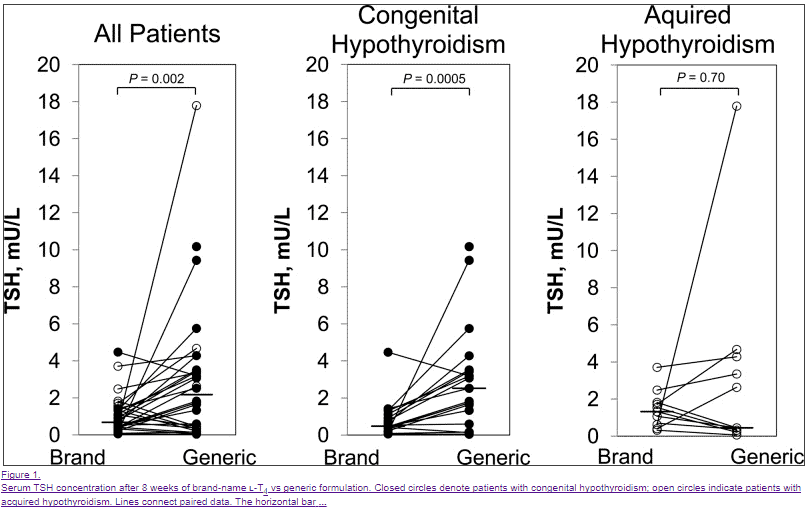

For the purposes of the FDA, these medications are considered bioequivalent (10), meaning they should behave and act the same regardless of which type you are currently taking.

Both medications contain the active ingredient Thyroxine but they differ in the types and amounts of inert or inactive ingredients.

These inactive ingredients include various fillers, binders, and even color dyes to change the appearance of the medication.

What’s important here is that these inactive fillers, dyes, and binders may actually alter the absorption and serum stability of T4 and TSH (11).

Several studies have indeed shown that Synthroid and levothyroxine are not bioequivalent (12), but this difference tends to only show in very sensitive patients such as patients who have very little thyroid reserve (those without a thyroid or with complete thyroid gland damage from Hashimoto’s).

So why does this matter?

First:

This is very important because in the United States, your pharmacist can substitute Synthroid for levothyroxine which may cause issues for some patients.

So what can you do?

If you are taking Synthroid, (and it isn’t working for you) you can request that your physician prescribe levothyroxine and put on the prescription “dispense as written” which will force the pharmacy to fill the correct medication.

This is usually only an issue for patients who are prescribed Synthroid because the pharmacy may try to save money on insurance by altering the prescription to the generic levothyroxine version.

Second:

Simply switching from Synthroid to levothyroxine or levothyroxine so Synthroid may actually provide more stable serum thyroid levels in your body and therefore reduce your symptoms.

This is worth considering for certain individuals who may be sensitive to the differences in the inactive ingredients of these medications.

#6. There Are Cleaner Options Available That May Work Better

Sometimes it’s just nice to have options when it comes to medications.

We’ve discussed that some people may do better when switching from Synthroid to levothyroxine or vice versa, but there may actually be a better option and that’s Tirosint.

Tirosint is unique among T4-only thyroid medications in that it only has 4 ingredients.

3 inactive ingredients (Gelatin, Glycerin, and Water) and 1 active ingredient (Thyroxine).

Compare this Synthroid which has a lot more (I’m not counting but you can see the chart below):

What does this mean for you?

It means that certain individuals with known conditions may benefit from the use of Tirosint over traditional medications such as levothyroxine and Synthroid.

This list includes patients who may fall into the following categories:

- Patients with gastrointestinal issues such as acid reflux, low stomach acid, IBS, IBD, SIBO/SIFO

- Patients who have experienced unexplained symptoms while taking Synthroid/levothyroxine such as rash, headache, or an upset stomach

- Patients who have not experienced significant symptomatic resolution while taking Synthroid

- Patients with decreased intestinal motility or gastroparesis

- Patients with known sensitivities to multiple medications, foods, etc.

If you fall into the categories listed above then switching from Synthroid to Tirosint may be worth exploring with your current physician.

You can also read more about Tirosint in this guide.

#7. Synthroid Only Works If You Take Enough

This is a debated topic but it’s worth mentioning here so that you are informed from the perspective of the patient.

As you’ve probably noticed your dose of thyroid medication is usually determined by your serum value of TSH.

But what is TSH?

TSH stands for thyroid stimulating hormone and it is secreted by your pituitary gland.

The function of TSH is to act on thyroid glandular tissue and stimulate the release of T4 and T3 thyroid hormones.

When you aren’t taking thyroid medication you can use the TSH to diagnose hypothyroidism.

If you aren’t producing enough thyroid hormone from your thyroid gland (either from conditions like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, some nutrient deficiency, or because you don’t have one) your TSH will start to increase or elevate.

When your TSH reaches a certain point, usually around 5-10 mIU/L, you are diagnosed with hypothyroidism and your TSH is said to be too high.

At this point, you are usually placed on thyroid medication such as Synthroid which will cause your TSH to drop or lower.

Your dose is then adjusted until you reach some TSH that your physician feels is “optimal” for you and based on other factors such as your symptoms.

This all sounds great in theory but the problem comes when we try to outline what is an “optimal” TSH level.

Most physicians tend to believe that a TSH of less than 5.0 mIU/L is probably sufficient, while newer studies indicate that a more healthy TSH is probably less than 2.0 to 2.5 mIU/L (13).

Things get even more complicated when you consider that a healthy TSH may actually be closer to 1.0 when you remove confounding variables such as the presence of Hashimoto’s in the data sample when these numbers were being determined.

The moral of the story is this:

If you are taking Synthroid and your TSH is not close to 1.0 to 2.0 mIU/L, it may be that you are underdosed or not taking a sufficient amount for your body.

While the TSH may be helpful, it’s certainly not the only thyroid lab test that you should be ordering or that can help you determine your dose (but more on that below).

#8. You May Do Better On Other Thyroid Medications

Sometimes you have to know when enough is enough.

And what I mean by that is sometimes it doesn’t make sense to stay on Synthroid or levothyroxine if it simply isn’t working for your body.

Many patients find themselves in a situation where they are continually adjusting their Synthroid dose based on their TSH but they never actually feel better.

It’s like playing a never-ending game of whack-a-mole but without some prize at the end.

So let’s be straightforward here:

Some patients will simply not do well on T4-only thyroid medications such as Synthroid.

In these patients (roughly estimated to be around 15% of all patients with hypothyroidism (14)) thyroid conversion may be blunted in a situation that results in low free T3 and total T3 levels.

It’s not exactly clear why this occurs in this subset of people but it is likely related to genetic factors and the efficiency of a very important enzyme family known as deiodinases.

What is known (at least subjectively) is that treating these patients with medications that contain T3 tends to result in dramatic symptomatic improvement.

These patients often experience more weight loss (15), a better quality of life, less depression, and higher serum T3 levels in the blood.

Medications that contain the active thyroid hormone T3 include liothyronine, Cytomel, and formulations of Natural Desiccated Thyroid.

These medications can easily (relatively) be added to your existing dose of thyroid medication and can be taken concurrently with Synthroid.

And to put this into perspective that means roughly 1 out of every 6 to 7 people will need T3 in some form added to their regimen.

If you consider that the US population is around 325 million people of which about 10% have hypothyroidism that means around 32.5 million people suffer from this disease.

If you take 15% of that number (the number of patients who have thyroid conversion issues) it’s around 4.875 million people who may need T3 medication.

That’s quite a bit!

#9. Get These Tests To Make Sure Synthroid is Working

It should come as no surprise that you need more than just a TSH to evaluate thyroid function in your body.

The TSH falls short as a universal marker of thyroid function in the body because it lacks the same deiodinases that exist in other peripheral tissues (16).

This means that the sensitivity of the pituitary gland (and therefore serum TSH levels) is different from those of other tissues making it a poor marker of thyroid saturation in distant tissues.

It also says relatively little about the peripheral conversion status of the individual or their genetics.

What does this mean for you?

It means that in order to have a more complete picture of what is happening in your body you will need more than just the “standard” TSH and free T4.

It doesn’t mean that the TSH is useless, not by a long shot.

The TSH can be still used as a sensitive marker for the identification of hypothyroidism initially, but it shouldn’t be used as the sole marker in thyroid hormone management.

Instead, you will get a more clear picture if you use the following tests:

- Total T3 – The total T3 is a marker of T3 in the body that is bound and represents a larger fraction than the free T3 portion.

- Free T3 – The smaller but more readily and biologically active form of T3 in the bloodstream.

- Free T4 – A reservoir for T3 conversion in the serum.

- Reverse T3 – An antithyroid metabolite that competes with T3 for cellular binding.

Common patterns of thyroid lab tests in individuals:

- High TSH while taking Synthroid – This is generally a sign that your dose is too low.

- Low TSH while taking Synthroid – This is generally a sign that your dose of Synthroid is too high.

- Normal TSH while taking Synthroid but with symptoms such as hair loss, cold intolerance, and constipation – This may be an early indication of poor peripheral thyroid conversion but more testing is required to determine this.

- Normal TSH with weight gain – You may be suffering from thyroid conversion issues or another hormone imbalance such as leptin resistance or insulin resistance.

- Normal TSH, normal free T4 with Low free T3, and low total T3 – This pattern may be indicative of poor thyroid conversion of low T3 syndrome.

- Normal lab studies but with elevated reverse T3 – Early thyroid dysfunction that is often seen in patients who have recently undergone calorie-restricted diets such as the HCG diet. Patients also under extreme stress will also show this profile (emotional, physical, or psychological stress).

If you are taking Synthroid, make sure you get a full lab panel to ensure you are properly analyzing your results.

Failure to check something like Total T3 or free T3 may leave you confused and confound existing lab tests and symptoms.

#10. Did You Know About These Side Effects?

Whenever you take Synthroid (or any medication for that matter) it’s always important to understand the side effects of that medication.

Hormones are always difficult to dose because the reason you are taking a hormone is that you are deficient in some specific hormone.

The problem is that the deficiency of the hormone causes side effects but the medication (or hormone) that you take to fix the problem also causes side effects.

So you may be left in a situation wondering if your side effects are from the deficiency or from the hormone you are taking to treat the deficiency!

This can get tricky, depending on the hormone, and this concept holds true for Synthroid.

Synthroid has some very troubling side effects which may mimic the side effects of hypothyroidism.

For instance:

Synthroid is known to cause hair loss by itself and hypothyroidism is also known to cause hair loss.

So what happens if you experience hair loss while taking Synthroid?

You have to figure out if it’s because of the Synthroid or your thyroid or both (You can learn more about how to treat hair loss in this guide)!

Sometimes the answer is simply taking more Synthroid and other times the answer is to stop taking Synthroid – you have to tease it out.

With this in mind I’ve put together a list of common side effects associated with Synthroid:

- Weight Gain – May be directly related to dose or thyroid conversion issues in certain individuals (read more about how levothyroxine may cause weight gain in certain individuals)

- Hair loss – Hair loss can be directly caused by thyroid medication or it can be the result of insufficient thyroid hormone (making it difficult to diagnose)

- Heart palpitations – Usually dose-dependent and related to too much thyroid medication

- Rashes – Usually the result of reactions to inactive fillers or dyes, may subside over time or when switching to “cleaner” formulations such as Tirosint

- Headaches – Usually be dose-dependent

- Insomnia – Usually be dose-dependent

- Hot flashes – Dose-dependent and usually an indication that your dose is too high

- Changes in the menstrual cycle – Usually part of the normal adaptive response as your body normalizes (usually subsides within a few months)

Remember:

You need to always consider the beneficial side effects as well as the unwanted (negative) side effects associated with any medication or hormone that you take.

Final Thoughts

Synthroid is one of many thyroid hormone replacement medications that exist.

While it may work for many people, there are many people who may require different medications and different combinations of T4/T3.

If you are taking Synthroid, make sure that you at least consider the 10 tips discussed in this article as they may be able to help you feel better.

Simply switching the type of T4 medication you are on or altering the time of day that you take your medication may be able to improve your thyroid status.

And now I want to hear from you:

Are you taking Synthroid?

Is it currently working for you?

Do you think you may need to switch or alter your thyroid medication to feel better?

Leave your comments below!

Scientific References

#1. https://doaj.org/article/94f813cafce84ed8b3558f063ef6604c

#2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28632526

#3. http://www.jscimedcentral.com/Endocrinology/endocrinology-2-1055.pdf

#4. https://www.restartmed.com/hypothyroidism/

#5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3092723/#B12

#6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3092723/

#7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2758731/

#8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21149757

#9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3139142/

#10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9103344

#11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9103344

#12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3565118/

#13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19941233

#14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5772692/

#15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3205882/

#16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1578599/

#17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8903695

#18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7340700

#19. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19961039