Euthyroid sick syndrome is a series of lab abnormalities seen in certain people with an acute or chronic illness.

Understanding this condition can help explain why so many thyroid patients are unhappy with their current treatment and help us (Doctors and patients) change how we evaluate thyroid treatment.

In this guide you will learn what ESS is, how it presents, what causes it, and if you should be treated if you have this condition:

What is Euthyroid Sick Syndrome?

If you have thyroid disease there’s a good chance you may not even be familiar with the term euthyroid sick syndrome.

But this syndrome is actually incredibly important because the physiology involved in this disorder can shed light on why our current thyroid treatment paradigm is lacking.

This condition is also referred to as nonthyroidal illness syndrome or NTIS for short.

But the name can be somewhat confusing so let’s unpack it to better understand the definition.

Euthyroid is a term used to describe a state of normal thyroid function in the body.

‘Sick’ refers to a condition that the patient is under and ‘syndrome’ is simply a word to describe a medical state.

So euthyroid sick syndrome can be re-stated as normal thyroid function seen in sick patients.

It is very clear, and MOST (if not all) doctors should be aware of this, that illness results in very specific changes to thyroid function that can be seen during routine blood tests.

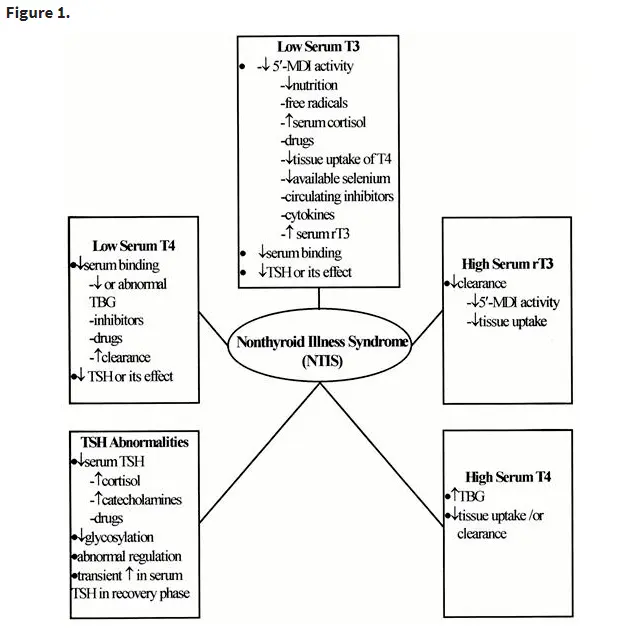

Patients with euthyroid sick syndrome present with very specific lab tests which have been classified as the following:

- Low T3 syndrome (or low serum T3 upon lab testing)

- Low T3-low T4 syndrome (sometimes both T4 and T3 are low)

- High T4 syndrome (another name for the same condition)

It is very clear that illness and chronic medical conditions result in these changes to thyroid function which dramatically alter the amount of free circulating thyroid hormone in the body.

This is the primary reason that Doctors do not order routine thyroid tests on patients who are admitted to the hospital.

The idea behind this condition is that there is some altered state of thyroid function that occurs due to illness.

Our current understanding of this condition is that it represents a state of “normal thyroid function” even though your lab tests are abnormal.

It is believed that changes, due to illness, negatively impact the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in such a way that suppresses TRH and TSH production leading to reduced stimulation of the thyroid gland and thus low circulating free thyroid hormones (2).

It’s also probable that illness alters thyroid hormone binding levels in the serum, thyroid hormone metabolism, and the uptake of thyroid hormone by specific tissues.

After all, we are simply talking about physiology here.

This begs the question though:

Is it possible to have euthyroid sick syndrome-like changes in those who suffer from CHRONIC medical conditions?

And do those changes affect thyroid function negatively to the point that they warrant treatment?

DOWNLOAD FREE RESOURCES

Foods to Avoid if you Have Thyroid Problems:

I’ve found that these 10 foods cause the most problems for thyroid patients. Learn which foods you should avoid if you have thyroid disease of any type.

The Complete List of Thyroid Lab tests:

The list includes optimal ranges, normal ranges, and the complete list of tests you need to diagnose and manage thyroid disease correctly!

Does ESS Cause Symptoms?

Because ESS is considered a state of “normal thyroid function” you actually wouldn’t expect people to have symptoms associated with thyroid disease if they also have ESS.

This may make sense in the acute setting, but it may fall apart in the chronic setting.

If you are a patient admitted to the hospital with sepsis or some other critical illness, it may not be easy to identify the cause of your fatigue or lack of energy.

Your symptoms could easily be attributed to your acute illness.

But in the chronic setting, we see something different entirely.

Some of these lab abnormalities may also be associated with abnormal hypothyroid-esque symptoms.

If you have low T3, low T4, or high reverse T3 then you may experience some of the following symptoms:

- Weight gain

- Cold intolerance

- Pain

- Hair loss

- Cold body temperature

- Slow heart rate

- Menstrual problems

- Fatigue or low-energy

Again, it’s important to realize that not all people with ESS will experience any symptoms.

But it’s equally important to understand that some people may experience hypothyroid symptoms and it is these people that may require treatment (more on that below).

What causes Chronic Changes to Thyroid Function?

Why does your body have a mechanism built-in to blunt thyroid function under certain circumstances?

The answer is not clear, but a few theories have emerged.

One such theory would be that, in an attempt to conserve energy, your body temporarily blunts

This makes sense in acute illness.

Why would your body want to put power and energy into growing your hair, maintaining the quality of your skin, and so on, if you are currently critically ill and about to die?

Wouldn’t it make more sense to put energy into bolstering your immune system (if you are suffering from an infection), improving cardiac output (if you are suffering from heart issues), or putting energy into healing after surgery (if you are suffering from a wound or trauma)?

Your body is much smarter than you probably realize and it does all of these things without you even thinking about it.

In response to illness, your body sends signals to the peripheral tissues to reduce the conversion of thyroid hormone into the active T3 thyroid hormone.

This results in normal to high levels of T4, low levels of T3, and high levels of reverse T3 (5).

This allows your body to titrate how it is expending energy, where energy expenditure should go, and probably helps the body to heal.

All of this information makes a lot of sense if we are talking about a critically ill patient, someone who is in the hospital with a serious problem, but what about patients who are “at home” but still chronically ill?

Is it possible that patients who have multiple illnesses may suffer from a similar set of problems as those people who are critically ill, but perhaps on a different scale or intensity?

This is exactly what I believe is going on in many patients.

Consider this example:

What if you are a middle-aged (40-50) female who is 50 pounds overweight?

Maybe you also have prediabetes (6), high cholesterol, slight inflammation in your body, and thyroid disease (7).

Is it possible that these metabolic abnormalities are putting strain on the body?

Perhaps enough strain to result in changes in thyroid function and thyroid conversion as your body attempts to fix the many problems you are facing?

While there are MANY reasons that you may have thyroid dysfunction, I believe that one of the most underappreciated conditions that some patients suffer from is low T3 syndrome caused by a chronic ESS-like state.

This type of syndrome will often be ignored or misdiagnosed by physicians because it doesn’t fit the current template of thyroid disease.

Low T3 vs. Euthyroid Sick Syndrome

Low T3 syndrome is a state of thyroid disease that is becoming more and more common.

You can think of low T3 as a subset of thyroid disorders that falls within the classification of euthyroid sick syndrome.

The same issues that cause ESS probably cause low T3, but each person may present with slightly different lab studies.

If we took 10 people and put them under extreme stress we might find that 4 out of the 10 people develop very low T3 levels while 4 out of the 10 people develop both low T3 and low T4.

In this way, they are probably variations of the same condition but altered by genetic factors at the individual level.

The problem with this condition is that it’s felt to be caused by factors unrelated to thyroid control (such as suppression of the pituitary gland).

Because of these changes, it is felt that low T3 syndrome is not primarily a thyroid disease.

And while this is true, it doesn’t mean that the person suffering from the condition will get the help they need.

If your low T3 is caused by inflammation (9), gut dysfunction (10), or nutrient deficiencies, then the only way that it will go away is if you address those problems.

But when was the last time that your Doctor asked you about any of these?

Should it be Treated?

Our current understanding of ESS is that patients with this condition should NOT be treated by thyroid hormone.

Studies have shown that giving patients T4 thyroid medications, even those who are critically ill, shows no benefit.

Other studies have shown, however, that the temporary use of T3-containing medications (such as liothyronine or Cytomel) may have some benefits in certain patients.

In the acute setting, the answer is more clear.

Treatment will probably not yield better results (12).

But what about in the chronic setting?

What about the person who has low T3 and who is ALSO experiencing hypothyroid symptoms?

This is probably the person who WILL benefit from thyroid hormone replacement (with T3-containing medications).

Euthyroid sick syndrome is said to be a state of euthyroidism (meaning normal thyroid function) but this name may be a misnomer under certain conditions (13).

It’s entirely possible that in some situations the thyroid lab abnormalities seen in ESS represent normal physiologic changes due to acute illness.

But it’s also possible that chronic suppression of thyroid function, such as seen with chronic medical conditions, may be a pathologic state which would benefit from thyroid hormone treatment.

So should you be treated if you have low T3 syndrome or euthyroid sick syndrome?

The answer probably depends on the degree of thyroid lab abnormalities that you are experiencing AND if you are also experiencing symptoms associated with your disease.

In patients who have hypothyroid symptoms (such as weight gain, fatigue, hair loss, constipation, and so on) and low T3, low T4, and high reverse T3, thyroid hormone replacement therapy may be beneficial or even necessary.

Whenever possible, your goal should be to treat underlying dysfunction which may cause the abnormal lab results, but in some cases, this may not be possible.

For those who fall into this category, supplementation with T3 medication such as liothyronine or Cytomel may be very helpful.

The changes we’ve discussed here may explain why studies do show that very specific people have a robust response to T3 medication while experiencing no benefit when using T4 medication.

Final Thoughts

It appears that our current understanding of thyroid function and physiology has some room to grow.

By understanding what happens in euthyroid sick syndrome and in acute illness, we can better understand chronic illness and thyroid hormone dysfunction among patients who are suffering.

There is a large sub-group of the population with thyroid disease who experience the symptoms of hypothyroidism but still remain untreated due to a normal TSH.

This population of people may be suffering from a chronic form of ESS, one which may be dramatically improved with the right treatment.

I remain convinced that this type of information will become more common over the coming years and patients will have much better outcomes as we expand beyond the current thyroid treatment paradigm.

Now I want to hear from you:

Do you have low T3 syndrome or do you suspect you have euthyroid sick syndrome?

Have you been able to get treatment or find relief with any other therapies?

What has worked for you? What hasn’t?

Leave your comments below!

Scientific References

#1. https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/82/2/329/2823087

#2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4979220/

#3. https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/82/2/329/2823087

#4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3887425/

#5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8808092

#6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5043536/

#7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5471726/

#8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4590373/

#9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27051079

#10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20351569

#11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4772089/

#12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19007679

#13. https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/82/2/329/2823087