While it is possible to test for cortisol, is it even helpful?

The answer is both yes and no which is why this topic deserves a deep dive into adrenal fatigue and cortisol testing.

In this article you’ll learn:

- Why adrenal fatigue is so controversial and why many doctors do not believe it exists.

- Why testing cortisol is not as straightforward as you may think and may not be accurate for evaluating stress.

- The various ways to test for cortisol (serum, salivary, and urinary).

- Why I recommend starting with serum cortisol over the other options.

- How your cortisol result influences your treatment and therapies for high/low cortisol.

Adrenal Fatigue: Let’s Talk About the Basics

Apparently, it’s not possible nowadays to have a discussion about a controversial topic without at least mentioning the other side of the argument.

And when it comes to adrenal fatigue, there is quite a bit of controversy (1).

The diagnosis of adrenal fatigue is not recognized by conventional doctors, but despite the fact that they don’t recognize it as a credible medical condition there are a great many people who experience the symptoms associated with this condition.

It would be foolish to disregard the experience of hundreds of thousands (possibly millions) of patients who experience the symptoms associated with the condition known as adrenal fatigue, but it’s also a good idea to maintain some degree of skepticism in any controversial topic.

What is not controversial about this condition is the fact that patients experience certain symptoms.

You can never deny the subjective symptoms that patients experience.

What you can deny, though, is that this condition results in some change or alteration to the stress hormone cortisol.

Cortisol, as many of you may know, is considered the “stress” hormone of your body.

During times of stress we know, from studying physiology, that cortisol is secreted and alters your physiologic state to allow your body to compensate for the stress.

Alternative providers believe that over time continued stress can cause disturbances to your cortisol level which can then be measured in various ways.

Whereas conventional doctors (primary care physicians and even endocrinologists) do not believe that this is the case nor that you can diagnose adrenal fatigue by testing cortisol.

So we have somewhat of a standstill.

Your standard doctor will likely not be willing to check your cortisol but your alternative doctor may.

So what’s the real story?

It turns out that both sides are partially true and that the real truth is somewhere in the middle.

Is it true that long-term stress can cause disturbances to your cortisol?

Yes, it can definitely happen but it doesn’t ALWAYS happen.

Is adrenal fatigue a fake disease that doesn’t exist?

This is obviously inaccurate because we have documented conditions where we KNOW (for a fact) that stress can lead to physiologic changes that cause the symptoms associated with adrenal fatigue.

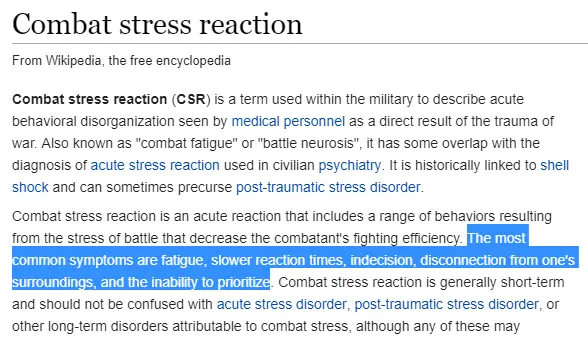

One of the most obvious conditions is known as combat fatigue or combat stress reaction.

It turns out that being in a war is fairly stressful to the body and combat veterans may experience symptoms that are very similar to what you probably know as adrenal fatigue.

Furthermore, we have another condition known as “burnout syndrome” which is well-established in the medical literature (2).

Doctors are notorious for experiencing this condition and would probably be served by reading this article and the therapies that are used to treat adrenal fatigue (though they are unlikely to do that).

Is it true that you can test for adrenal fatigue using various tests that evaluate cortisol?

This is probably mostly false as stress does not consistently affect serum/salivary/urinary cortisol levels.

While stress has the potential to do this it doesn’t appear that it happens with enough frequency to say one way or the other.

This can leave you, as the patient, in somewhat of an unsteady middle ground wondering what you should be doing if you experience the symptoms of adrenal fatigue.

And that’s the purpose of this article. To help you understand what (if any) tests are available to you to help you figure out what is happening in your body.

The Accuracy of Cortisol Testing

As we discussed, cortisol is thought of as the primary stress hormone.

It makes sense then that you might have abnormalities in your cortisol level if you are under constant stress.

And while that may sound intuitive, it turns out to not really be true.

Despite a number of studies and tests, there have not been any that definitively prove a connection between cortisol and stress.

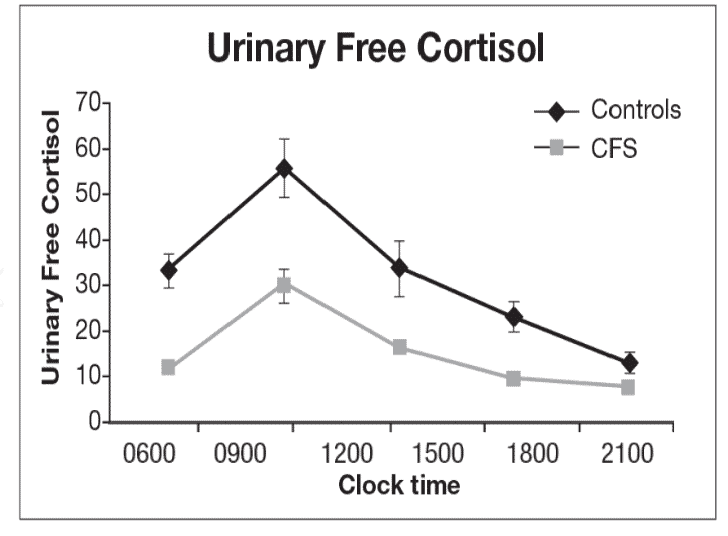

You can find some studies which show that stress is associated with lower cortisol (3) and you can find others that it can also cause a dramatic rise in cortisol (4).

But you just don’t find long-term studies that prove a precise connection between cortisol and stress.

It’s undeniable that there is a connection between stress and cortisol, we just don’t quite understand how it works yet.

Does this mean that all adrenal fatigue isn’t real or that all cortisol tests are invalid?

Not by a long shot.

But it does mean that you should be aware of what you are testing for and have realistic expectations when you get tested.

Why does cortisol seem to fall short when comparing the stress you are under and how your body responds to that stress?

#1. Stress impacts other systems in your body.

The connection between stress and how it impacts cortisol is not as neat as it might sound.

It sounds intuitive that if your body is under stress it will produce cortisol to combat the stress.

It also sounds intuitive that if you are under a lot of stress, eventually your body won’t be able to produce cortisol anymore because it becomes ‘fatigued’.

These concepts sound intuitive and they make sense.

But that’s just not what we see.

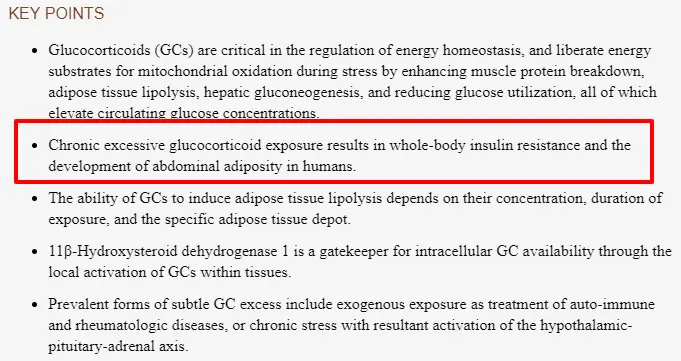

Instead, we see that while stress does impact your cortisol it also affects many other systems in your body.

Stress alters your heart rate, your blood pressure, how much thyroid hormone you produce, and your insulin levels.

These in turn may also interact with cortisol.

The net result is a complex system that can’t be broken down into one variable (cortisol) as many providers and patients believe.

Does that mean we should ignore cortisol? No, but it does mean that we should look at cortisol in conjunction with these other systems when assessing the impact of stress on the body.

#2. Stress impacts cortisol in different ways.

Complicating the picture further is the fact that even when stress affects cortisol it’s not clear how exactly it does this.

For instance:

There are no fewer than 3 ways that stress could be altering your cortisol and it isn’t even possible to test for all of these conditions.

Chronic stress could impact your total cortisol level by either raising it or lowering it.

But it could also affect how sensitive your cells are to cortisol.

This would be known as cortisol resistance and is a top contender (in my book) for one of the major ways that stress could impact cortisol.

If stress made your cells more resistant to cortisol then you could experience the symptoms of adrenal fatigue while testing “normal” for cortisol.

Isn’t this the position that many patients find themselves in?

They are convinced they have adrenal fatigue because their symptoms suggest it and yet their lab tests are normal.

Cortisol resistance could be a potential explanation for this phenomenon and there are studies to suggest that it may be playing a role (5).

Even with all of these variables and difficulties in evaluating cortisol, it’s still a good idea to at least consider testing (more on that below).

Tests Available for Adrenal Fatigue

There are 3 main ways to test your cortisol level:

- Serum Cortisol – Perhaps the easiest way to test your cortisol is by drawing your blood.

- Salivary Cortisol – Salivary cortisol is tested by assessing cortisol in your saliva.

- Urinary Cortisol – Urinary cortisol can be ordered and checked by looking at how much cortisol and cortisone are excreted in your urine.

Each of these methods has pros and cons.

Serum levels of cortisol can be difficult to evaluate because serum levels are not standardized and vary across hospitals (6) and other clinical studies.

Salivary cortisol levels suffer because they may not be indicative of cortisol levels (7) in other areas of your body and because many different medications and substances interfere with the test.

And urinary cortisol may not be accurate because the amount of hormone that you secrete may not reflect utilization in other tissues (8).

Of the three listed here, I almost always recommend starting with serum cortisol.

Why?

Because it’s cheap and almost always covered by insurance.

It may not be the ‘best’ or most accurate indicator of cortisol usage in your body but, as we will soon find out, that might not even be necessary.

Both urinary and salivary cortisol can be ordered by physicians as well but they are typically not covered by insurance meaning you will most likely have to pay out of pocket.

These tests are usually performed by ‘specialty’ labs which are different from the standard lab companies which run almost all of the blood tests you are used to.

In some cases, you can purchase these tests yourself, without the need for a doctor’s prescription, but beware that your conventional doctor is not likely to put much stock in the results and they may dismiss the test entirely.

It’s not uncommon for patients to get serum cortisol drawn, and find out that their serum cortisol is completely normal, only to check either their urinary or salivary cortisol to see if something shows up on these tests.

I’ve had numerous patients give me all 3 cortisol tests with different results.

Some tests show that their cortisol is abnormal and others show that their cortisol is completely normal. Most of the time they don’t really understand what their results mean or how to use them.

This is obviously a problem for people who want to figure out what is wrong with them.

They are obviously feeling poorly and may even have many of the symptoms of adrenal fatigue, but don’t have a ‘definitive’ diagnosis because their conventional doctor doesn’t believe in the condition.

I see this type of scenario all too often and I don’t think it’s actually necessary.

It turns out that you probably don’t even need to rely on cortisol testing to figure out what is going on.

What Information does Testing Give you?

I think the most important aspect of testing for any disease is to not only know that you have the condition but to also learn more about your condition.

If you are interested in diagnosing and managing adrenal fatigue, because you suspect you have it, the first question you want to be answered is whether or not it’s present.

There’s only one problem with this when it comes to your adrenals:

There’s no consensus regarding which cortisol test is the most accurate.

That’s problem #1.

You have to understand the limitations of each test and what type of information you are actually getting from that test.

If you are testing your serum cortisol, which is generally how I recommend that you start, you aren’t necessarily getting accurate information about how stress is impacting your body.

Other measures, including your blood pressure, heart rate, and other hormones, may actually be better indicators of this.

This same problem exists for both salivary and urinary cortisol, even those that may give you a better understanding of how concentrated certain cells are with cortisol.

They still don’t give you the complete picture and may therefore be inaccurate.

But this isn’t even the only issue.

Let’s say you order a cortisol test and it comes back abnormal.

Now what?

That’s problem #2.

Once you have that information you better hope that the results you are getting are going to give you some idea of how or what you should be doing to fix the problem.

And the results from cortisol testing don’t really do that!

They are only really helpful if they are incredibly elevated (meaning you might have Cushing’s syndrome (9)) or incredibly low (meaning you might have adrenal insufficiency).

All of the values in between (of which there are many) don’t give you any insight as to how you should treat the condition.

What should you do with moderately low cortisol? What about moderately high cortisol?

What’s the difference in treatment between these two conditions?

The main goal of treatment, after you ensure that you don’t have one of the more serious conditions such as Cushing’s disease or Addison’s disease (10), is to simply address your stress.

And that’s exactly what we will talk about next:

Treating & Managing Adrenal Fatigue (Based on Testing)

I mentioned that your level of cortisol doesn’t really impact your treatment and I want to expand on that a little more here.

We’ve already alluded to the fact that conventional medicine doesn’t consider adrenal fatigue to be a real disease.

If you order a serum cortisol test and it comes back as low normal, what would your next steps be?

Obviously, you want to address and manage your stress, but what should you do beyond that?

There are many therapies available to treat adrenal fatigue (we will talk about some below), but none of them require specific knowledge of how high or low your cortisol is (with a few exceptions).

Most of the treatments available tend to help normalize or balance cortisol by helping your body become more resilient to stress.

This means that they can have a lowering or an elevating effect on your cortisol depending on the situation.

So in a way, it’s not always necessary or required to test your cortisol before you think about treatment.

Do you really need to test your cortisol to know that you should be sleeping more, eating better, working fewer hours, exercising daily, or taking more vacations?

I suppose some of you might, but the majority do not.

I can tell you right now that you should be doing these things and they will likely have some impact on your stress, for the better!

What about supplements? What role do they play?

This is where it can be beneficial to know and understand how you should approach management.

The emphasis can be beneficial because it’s rarely required.

There are some supplements that can actually act to help improve your cortisol level if it is low, and on the opposite side, there are some specific supplements that can help lower your cortisol if it is too high.

These supplements should always be paired with the lifestyle changes mentioned above (including changes to your diet).

Some specific therapies which can help INCREASE cortisol include:

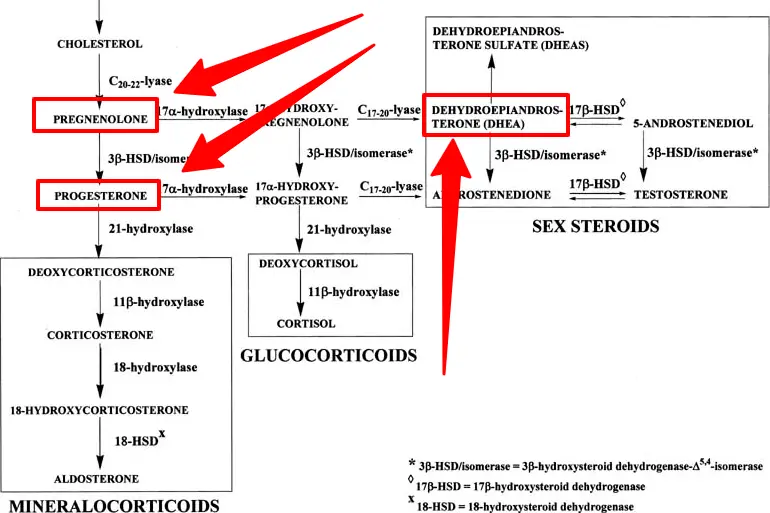

- DHEA – DHEA is sometimes recommended for adrenal fatigue as it is high up in the steroid metabolism pathway. Some studies show that daily use does impact sex hormone production in the adrenal gland (11).

- Pregnenolone & Progesterone – These precursors are sometimes used to try and help stimulate the production of other hormones such as cortisol (12). Theoretically, taking these supplements may improve cortisol (depending on steroid metabolism) though studies have not shown this to be the case.

- Hydrocortisone – Hydrocortisone is a prescription medication that contains the hormone cortisol. It is sometimes recommended for those with low serum cortisol levels.

- Adrenal glandulars – Adrenal glandulars contain animal adrenal glands which contain proteins, enzymes, and other hormone precursors that may help your adrenal gland function.

Some specific therapies which can help DECREASE cortisol include:

- Phosphatidylserine – Some studies have shown that PS may help curb the rise in cortisol seen in exercise (13). I’ve used this supplement with varying degrees of success in non-exercise-related cortisol elevation.

- Melatonin – Melatonin may help improve cortisol levels in those suffering from sleep-related (14) issues or in those who are old (sleep quality declines with age).

Other therapies which can be used regardless of whether your cortisol is high or low include:

- Dietary changes – Eating a diet that is high in refined carbohydrates and sugars is not going to do you any good. Stick to real whole foods with moderate carbs (unless you struggle with high blood sugar).

- Exercise – Exercising regularly (but not too much) will help your body tolerate stress. Excessive exercise, however, can actually add to stress and may be causing problems for you if you also have stress from other sources.

- Reduced caffeine intake – Caffeine can help keep you stimulated but it can also diminish the quality of your sleep which is not ideal if you are already stressed out. Cut out caffeine 100% if possible.

- Sleeping more – A lack of sleep may contribute to changes in cortisol and negatively impact your health in a variety of ways.

- Relaxing more – Focus on taking breaks and doing things you enjoy. It’s particularly therapeutic to go outside to get your mind off of the day-to-day things that cause minor stress.

- Reducing stress – If possible, do your best to eliminate or avoid stress as much as possible (this may not be possible but do it if you can).

- Adrenal adaptogens – Adrenal supplements, especially adrenal adaptogens, have been studied and shown to be effective in helping people manage stress. Some of these therapies, such as ashwagandha, have been around for centuries.

- B Vitamins – B vitamins can help promote energy production and many people who are not sleeping enough or feeling fatigued may benefit from supplementation with pre-methylated B vitamins.

- Multivitamins – Multivitamins can be great if you haven’t taken one in a while. They contain a number of nutrients that are required for all sorts of functions in your body. Find a quality multivitamin to help replete all nutrient levels.

This isn’t an exhaustive list of all therapies available but it should get you heading in the right direction.

Recap + Final Thoughts

What should you take away after reading this article?

My hope is that you understand, with some degree of certainty, that cortisol testing is not a straightforward process.

In addition, I want you to realize that if you think you have adrenal fatigue it may not even be necessary to check your cortisol levels to confirm your suspicion.

Why?

Because many of the therapies designed to help treat adrenal fatigue can be done regardless of your cortisol level.

In fact, most of these therapies may just help you lead a healthier life that is more resistant to stress.

There are only a handful of therapies that can help treat either high or low cortisol.

If possible, I think it’s a good idea to check at least your serum cortisol.

You can do this when you test for other hormone imbalances such as thyroid problems (15) and insulin resistance (16) which tend to accompany people who suffer from chronic stress.

These conditions should be tested for (it’s just good medicine) and you might as well throw in serum cortisol in the process.

If you find that your cortisol is normal, however, don’t be discouraged.

The fact that your cortisol is normal doesn’t preclude you from suffering from stress in a way that may lead to the symptoms of adrenal fatigue or burnout syndrome.

Do your best to stick to well-studied therapies to treat adrenal fatigue and stay away from marketing claims that are too good to be true or incredibly expensive.

Now I want to hear from you:

Have you undergone testing for adrenal fatigue?

If so, what tests did you get done? What were your results?

What therapies have you tried?

Are you considering forgoing cortisol testing and just starting treatment?

Leave your questions and comments below!

Scientific References

#1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4997656/

#2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279286/

#3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3774738/

#4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2249754/

#5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3341031/

#6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17389462/

#7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3335961/

#8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4280712/

#9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279088/

#10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3636818/

#11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17145649

#12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3427920/

#13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2503954/

#14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19301769

#15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21032895

#16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3942672/